by Nomad

When people say they believe every word of the Bible, they may not know very much about the history of the sacred text they claim as the direct word of God.

When people say they believe every word of the Bible, they may not know very much about the history of the sacred text they claim as the direct word of God.

As Moses climbed down from the mountaintop with his ten commandments, the amazed Israelites noticed a great change in his appearance. The question is: did Moses have newly white hair? Or did he had a pair of horns on his forehead?

The answer to that depended on which period of history you lived in. For most of us, it's not a subject we would normally dwell on. But those who claim the Bible is the infallible Word of God, the question presents some thorny problems.

Moses with Horns

Above is a detail photo of a statue from the end of the Middle Ages. This statue of Moses was sculpted by Michelangelo between the years 1513–1515. Today, it sits in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome.

You might see something a bit peculiar if you study the photo closely. Along with his flowing beard and tablets in his arms, the Prophet Moses has a pair of goatish horns on his head.

One could be forgiven for thinking that Michelangelo was shooting at a statue of Lucifer.

But no, that's the Hebrew lawgiver Michelangelo carved.

One could be forgiven for thinking that Michelangelo was shooting at a statue of Lucifer.

But no, that's the Hebrew lawgiver Michelangelo carved.

It's important to note that Michelangelo took absolutely no creative license when sculpting this work. And under their very critical eye, the Church from the pious to the priests, including Pope Julius II, saw nothing unusual in the artist's concept.

In fact, it was very much in keeping with the formal interpretation of the Bible. At that time. According to the devout during the Renaissance period, Moses went up to the mountain and came back with the Ten Commandments... and horns at the top of his forehead. (Another translation suggest rays of light came out of his forehead.)

In fact, it was very much in keeping with the formal interpretation of the Bible. At that time. According to the devout during the Renaissance period, Moses went up to the mountain and came back with the Ten Commandments... and horns at the top of his forehead. (Another translation suggest rays of light came out of his forehead.)

However, today the translation reads that Moses came down from Mount Sinai with a far less-jarring mane of white hair.

Here's the Hollywood version that we are most familiar with. Charlton Heston looking somewhat lupine, furry and divine. Not a smidgeon of horns.

This horned depiction was based on the Vulgate, the Latin translation of the Bible used when Michelangelo lived.

"And when Moses came down from the Mount Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord. And Aaron and the children of Israel seeing the face of Moses horned, were afraid to come near...And they saw that the face of Moses when he came out was horned [cornutam Vulgate], but he covered his face again, if at any time he spoke to them." (Exodus 34:29-35)

There are actually many examples of the horned Moses, mostly dating back to the 11th century.

The English intellectual Sir Thomas Browne noticed this problem in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or, Enquiries into Very many Received Tenets, and commonly Presumed Truths, back in 1646.

As a man of wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric, Browne debunked a number of legends, even of the religious variety. Browne was a man just ahead of his age, committed to the Age of Enlightenment, unafraid of what at the time was still called "the new learning".

"The ground of this absurdity was surely a mistake of the Hebrew Text."

He goes on to explain that the actual meaning was closer to "a radiant shine" rather than horns. Browne dismisses the problem (and its implications) pretty casually, claiming that "no injury is done unto Truth by this description."

* * *

That's true, of course. It could be dismissed as a quaint factoid of Church history. However, for Biblical literalists, this footnote of history presents some insurmountable problems.

Many people, even today, believe that the Bible cannot be questioned based on the idea that the text is the Word of God, written by the hand of men, divinely inspired. What is written is what is meant, word for word.

And that is all there is to it.

If that were true, some have long argued, then how can there possibly be any mistranslation or misinterpretation? How could Moses have ever had horns?

Why would God have allowed people to believe something that was so clearly incorrect or at least, inaccurate? Why would He have allowed any divergence of Holy Wisdom?

More gravely, such a misreading opens another question: what other passages of the Bible may now commonly misunderstood? If there was a mistranslation in the past, then why couldn't there be a mistranslation of the Bible in the future?

Why would God have allowed people to believe something that was so clearly incorrect or at least, inaccurate? Why would He have allowed any divergence of Holy Wisdom?

More gravely, such a misreading opens another question: what other passages of the Bible may now commonly misunderstood? If there was a mistranslation in the past, then why couldn't there be a mistranslation of the Bible in the future?

Saint Jerome's Conundrum

Most educated people in the Christian world are aware that the Bible has undergone many revisions.

Back in the early days of the Church, (383 A.D) Pope Damasus charged Saint Jerome to standardize and revise old Latin translations of the Holy Texts.

Jerome quickly understood the difficulties of his task at hand and wrote of his qualms to the Pope.

You urge me to revise the old Latin version, and, as it were, to sit in judgment on the copies of the Scriptures which are now scattered throughout the whole world; and, inasmuch as they differ from one another, you would have me decide which of them agree with the Greek original.

In this passage, it is clear that the texts were in conflict even at the inception of the religion. Even this passage calls into question whether the Holy Book can be considered faultless.

As a devout Christian, Jerome expressed his mixed feelings. The commission was both a labor of love but also "perilous and presumptuous."

Even for all of the best reasons, trying to create one definitive Holy text was bound to upset just about everybody.

A theological hot potato.

Is there a man, learned or unlearned, who will not, when he takes the volume into his hands, and perceives that what he reads does not suit his settled tastes, break out immediately into violent language, and call me a forger and a profane person for having the audacity to add anything to the ancient books, or to make any changes or corrections therein?

So, as an example, when such people read that marriage can only be between a man and woman, there is little room for challenging the holy texts. One must accept what has been written because what is written on the page is as though written in stone.

No more, no less and absolutely no argument.

At Variance

Of course, anybody who has ever tried to do any kind of translation instantly understands the problems with this view. Languages can often be imprecise vehicles for communicating ideas, especially when it comes to details. A single word can, for example, have several interpretations- even in the same language.

A translator often has to make judgements based on common sense and a general understanding of what the intent of the original writer.

People who know only one language may not understand how easily confusion can occur.

Now add a further complication: Imagine trying to translate a text not simply from one language to another but through many languages, such as Greek, Latin, Old English and finally Modern Day English.

Now add a further complication: Imagine trying to translate a text not simply from one language to another but through many languages, such as Greek, Latin, Old English and finally Modern Day English.

Jerome also noted that, despite the contention of modern day literalists, he found conflicts between existent versions back in the 4th Century. The readings, he warned the Pope, were "at variance with the early copies" and could not all be equally correct. And all of the texts could certainly not be accepted literally as the Word of God. In fact, he said that there were "almost as many forms of texts as there are copies."

Given that admission from Jerome, how could this variation be possible if the Bible were actually divinely-inspired, unalterable and infallible? Wouldn't there be only one text from the beginning, without any need for interpretation or "fixing"?

Jerome was particularly concerned with trying to standardize the conflicting texts of the New Testament. The Old Testament, he writes, had already been reviewed and largely codified by scholars long before. Even then, a horny Moses somehow managed to slip in.

In dealing with the New Testament, Saint Jerome searched for a solution by attempting to go back to the original Greek in order to:

correct the mistakes introduced by inaccurate translators, and the blundering alterations of confident but ignorant critics, and, further, all that has been inserted or changed by copyists more asleep than awake?

In other words, mistakes were made by careless translators. Again, that isn't plausible if the texts were the product of the Hand of God. Right?

Jerome mentioned in this letter to the Pope that "versions of Scripture which already exist in the languages of many nations show that their additions are false."

What? False. did he say?

But if it is the Word of God.. then.. um..

Again, Biblical literalists who put their faith solely in the unquestioned divinity word of God must explain how God would have possibly allowed such a thing to happen.

So in the end, Jerome was forced to revise by returning to the source documents. He attempted to sort things out by choosing only the earliest versions.

We must confess that as we have it in our language it is marked by discrepancies, and now that the stream is distributed into different channels we must go back to the fountainhead.

Despite poor Saint Jerome's evident care and delicacy, we still see that his flawed translation remained part of the Church orthodoxy for over a thousand years.

Moses had nubby little horns and that mistaken translation literally carved in stone.

The Rejected Gospels

Additionally, in the past some of the books, which were considered at one point every bit as sacred as the rest of the New Testament but have, at some time in the past, been removed from that category. At one time many early Christians believed these rejected books also to be the word of God.

(For a more or less complete list of those forgotten books, click here.)

(For a more or less complete list of those forgotten books, click here.)

According to some estimates, early Christians wrote at least twenty gospels that weren't included in the bible. Many of these non-biblical gospels apparently disappeared later, although it's possible that copies of some of them still survive at unknown locations. Luckily, several that appeared to be missing have been found again in modern times. But some are still missing, and could be permanently lost.

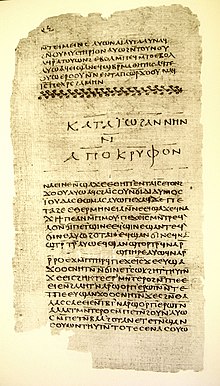

Take the Gospel of Thomas, as one notable example. Although it was widely referenced in other ancient sources, up until 1945, only three small fragments existed dating back to the second century.

Take the Gospel of Thomas, as one notable example. Although it was widely referenced in other ancient sources, up until 1945, only three small fragments existed dating back to the second century.Then the full text was discovered in the village of Nag Hammadi in Egypt. Today, despite the fact that this collection of 114 sayings of Jesus is "perhaps the earliest, most popular", and best "Gnostic" Gospel around, it has been rejected by the Church. (Some claim it to be a forgery but this is by no means the consensus opinion.)

According to Christian orthodoxy, it cannot be included since it was written in the second century. (As we have seen, however, the Bible was still being revised in the 4th century under Jerome. So that second-century cut-off date is a bit arbitrary, to say the least.)

At any rate, the rationale is that by that time, all of the apostles of Christianity had already died. However, there is yet another problem. The Gospel of Thomas was actually transcribed in the second century but actually written much earlier.

Some scholars even think this particular gospel may have been the source document for many of the other canonical books. Other researchers argue that this document was one of the earliest forms in which material about Jesus was handed down.

At any rate, the rationale is that by that time, all of the apostles of Christianity had already died. However, there is yet another problem. The Gospel of Thomas was actually transcribed in the second century but actually written much earlier.

Some scholars even think this particular gospel may have been the source document for many of the other canonical books. Other researchers argue that this document was one of the earliest forms in which material about Jesus was handed down.

In any case, it is, of course, a rather weak and strange argument. It suggests that God's Word (or His inspiration) was limited only to the apostles and only for a certain limited period of time. After that, the door closed. .

However, there are also problems with this idea too. Namely, it conflicts with the power of the Holy Spirit to move the hearts of humankind and give divine inspiration to every believer.

There is, according to this view, no point in discussing the matter because Biblical truth originates from the "inspired, inerrant Word of God."

However, the word "inerrant" means "incapable of being wrong" and as the horns of Moses demonstrates there is plenty of room for mistakes.

The historical record of how the Christian orthodoxy was established and which of the books were included in the New Testament also throws into doubt those claims.

Even though the evidence is pretty clear that Christianity and the New Testament are the product of humankind, Literalists carry on believing.

According to their view, God crafted the New Testament, guided the hands and moved the minds of the writers. Therefore, as mere mortals, we cannot question or reform or reject what has been inscribed.

There can be no lost or rejected books from the New Testament. As one source adamantly and definitively states:

End of story. so they say. To say otherwise is forbidden.Every book that God intended and inspired to be in the Bible is in the Bible. There are many legends and rumors of lost books, but there is no truth whatsoever to these stories.

There is, according to this view, no point in discussing the matter because Biblical truth originates from the "inspired, inerrant Word of God."

However, the word "inerrant" means "incapable of being wrong" and as the horns of Moses demonstrates there is plenty of room for mistakes.

The historical record of how the Christian orthodoxy was established and which of the books were included in the New Testament also throws into doubt those claims.

The Establishment of the Dogma and the Canon

On 19 June 325 AD, the Byzantium Emperor, Constantine the Great, the first Christian Emperor of Rome., brought together the highly influential Church fathers to sort out some nagging issues. As a state religion, Christianity of that time was not particularly promising.

This meeting, held in the modern day town of Iznik, Turkey, was called the First Council of Nicaea, bringing together some 300 Church leaders.

Before that, there was utter confusion. Some of the variants of Christianity were causing alarm, schisms and downright disgust amongst the leaders of the Church. Ideas that questioned the divinity of Christ, the virgin birth and the perplexing complications of the Trinity had become epidemic, for example.

As one Christian source states:

As one Christian source states:

Constantine prodded the 300 bishops in the council make a decision by majority vote defining who Jesus Christ is. The statement of doctrine they produced was one that all of Christianity would follow and obey, called the “Nicene Creed.”

It is surprising that God hadn't made that clear to all mankind before that time.

Seventy-years later on 28 August 397, came the Council of Carthage. At that meeting of Church leaders, the canon of Scripture was established. The proceedings were chronicled in the Codex Canonum Ecclesiæ Africanæ.

Of the New Testament: four books of the Gospels, one book of the Acts of the Apostles, thirteen Epistles of the Apostle Paul, one epistle of the same [writer] to the Hebrews, two Epistles of the Apostle Peter, three of John, one of James, one of Jude, one book of the Apocalypse of John.

Besides the books listed in the official Canonical Scriptures no other books, from that time forward were to be read in the Church under the title of divine Scriptures.

Books not on that list, like the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Truth, were considered forged or heretical or an offense against the orthodoxy of that age. For that reason, these texts were subject to suppression.

The Official Canon was confirmed by Pope Innocent I in 405 AD. In that year, the pope sent a letter to all bishops with a command to use only this list in all church ceremonies.

Books not on that list, like the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Truth, were considered forged or heretical or an offense against the orthodoxy of that age. For that reason, these texts were subject to suppression.

The Official Canon was confirmed by Pope Innocent I in 405 AD. In that year, the pope sent a letter to all bishops with a command to use only this list in all church ceremonies.

Adoptionism was a Christian belief that said Jesus was born as a mere (non-divine) man, was supremely virtuous. The much-despised belief called Arianism rejected the Trinity and that Jesus was not the Son of God. Think of the implications if either of those ideas had become a legitimate part of the Christian faith.

If the Bible were actually divinely-inspired, why would God have waited so long to establish an orthodoxy, a concise doctrine of the Christian faith? For nearly four hundred years, vast numbers of devout Christians were allowed to live and die (and presumably go to Hell) believing all the wrong things. Through no fault of their own.

Like the horns of Moses, this history tends to undermine all support for the view of the Biblical Literalists.

How so?

Whether defenders of an absolutist Christian interpretation like it or not, God's "oversight" had to be corrected the Church fathers in late 4th century when they were called upon to decide what belonged in the Holy Book and what would be consigned to the flames.

The Role Consensus Opinion Played

In order to support a literalist interpretation, one must rebut the idea that a group of men sat down and decided on their own what will be included in the New Testament. That's important because only a divine source of the Bible cannot be challenged by the skeptics.Bart D. Ehrman, an American New Testament scholar, states that the canon- that is which books belong under the title "The New Testament" was produced not by any council or official authority. Rather, Ehrman states,

“The canon of the New Testament was ratified by widespread consensus rather than by official proclamation."

That idea conflicts with the historical record. Even if the history actually supported Ehrman's ideas, it would present even more problems with the "divine inspiration" idea.

According to Ehrman, certain books were accepted into the canon of the New Testament simply because most people believed them to be true.

Think about that for a moment.

The New Testament wasn't handed down from heaven. It wasn't decided by a band of old men moved by the Holy Spirit. The canon of the New Testament was formed by a "broad and ancient majority opinion."It's what people believed and wanted to continue to believe.

Of course, that's exactly the same thing happening today.

According to Ehrman, certain books were accepted into the canon of the New Testament simply because most people believed them to be true.

Think about that for a moment.

The New Testament wasn't handed down from heaven. It wasn't decided by a band of old men moved by the Holy Spirit. The canon of the New Testament was formed by a "broad and ancient majority opinion."It's what people believed and wanted to continue to believe.

Of course, that's exactly the same thing happening today.

Why is all this Important?

A Gallup poll conducted last year revealed that 28 % percent of Americans believe the Bible is the actual word of God and that it should be taken literally. If that seems shocking to you, then there is brighter news to report too.

The survey pointed out:This is somewhat below the 38% to 40% seen in the late 1970s, and near the all-time low of 27% reached in 2001 and 2009.

Despite the number of Bible literalists, nearly half of Americans tend to hold less strict views on the subject, believing that Bible is the inspired word of God, not to be taken literally.

As we have seen, there is more than enough evidence to question that idea. Nevertheless, even today this notion is still widely promoted.

With some doomed logic, Literalists cite internal evidence to back up their claims:

In hundreds of passages, the Bible declares or takes the position explicitly or implicitly that it is nothing less than the very Word of God.

The Bible is the Word of God because... because.. well, because it says so. Such circular arguments can make your head spin.

Another supporting example that the Bible is the Word of God is the so-called the continuity of the Bible. They claim that, although it was written by "a wide diversity of authors (as many as 40)" it is not merely a collection of sixty-six books.

Firstly the diversity claim is questionable.

For instance, there are no women authors included in the Bible. Removing 50% of the population is obviously narrowing of that diversity feature. Most of the authors of the New Testament came from the same area of the world and lived in the same time period. How much diversity of thought could there be under those circumstances?

In that regard, it would be about the same as a group of white middle-aged Protestant males in Georgia coming together and writing a sacred text. Who could honestly claim diversity there?

For instance, there are no women authors included in the Bible. Removing 50% of the population is obviously narrowing of that diversity feature. Most of the authors of the New Testament came from the same area of the world and lived in the same time period. How much diversity of thought could there be under those circumstances?

In that regard, it would be about the same as a group of white middle-aged Protestant males in Georgia coming together and writing a sacred text. Who could honestly claim diversity there?

Besides that, this claim of continuity is also a bit deceptive. As we have seen, it was actually more like imposed conformity, dating back to the Early Church's first centuries. All who did not conform were considered heretics and expelled or worse. All books that did not meet with official approval were erased from history.

Another bit of "evidence" of the divinity of the Bible is its perfection. The late Dr. Lewis Sperry Chafer wrote that the Bible had to be the word of God because

“It is not such a book as man would write if he could, or could write if he would.”

It is, Chafer seemed to think, beyond the scope of man’s capacity to write such a book It's divine because it is too perfect?

When you think about it, that's a sad way of thinking. Mankind has produced an impressive list of great achievements in science and in the arts. It has cured )and is presently curing) diseases that have plagued humanity since man walked on two feet. Humankind, for all its flaws, has shown the capacity to produce many things very close to perfection.

To say otherwise is simply ignorance and a devaluation of humankind to the level of a dumb beast. Faith was supposed to help man reach a higher level of morality, to inspire and, not degrade him and create self-doubt.

To say otherwise is simply ignorance and a devaluation of humankind to the level of a dumb beast. Faith was supposed to help man reach a higher level of morality, to inspire and, not degrade him and create self-doubt.

(For a more complete list of the reasons Literalists feel that the Bible has to be the word of God, click here.)

Oddly enough, even the New Testament warns against blind obedience. According to 1 Corinthians, true faith came not from a book but through the Holy Spirit acting upon the consciences of moral men and women, "to each one is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good."

Later in the same passage, St. Paul advises to the congregation:

Brethren, do not be children in your thinking; yet in evil be infants, but in your thinking be mature.

That would require questioning and weighing issues in your heart, not merely following dictates in a Holy Book.

The Danger of Unquestioning Adherence to Holy Books

While believing these might seem harmless enough, there is a danger in accepting the Bible as the unquestionable divine word of God.

Rev. Wil Gafney, an associate professor of Hebrew and Old Testament at The Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, in an article in the New York Times observed:

Biblical literalism requires reading all of the Bible as being intended to relay a series of historical (and theological) facts.And even among Christians, there is no single Bible: there are different books in different sequence in Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant and Anglican Bibles.Literal readings of nonliteral texts can also lead to fraudulent readings, dogmatic tenacity to ahistorical or unscientific claims, and the loss of credibility for those who insist on nonsensical interpretations.

Meaning, a literal acceptance of every word in the Bible (or any Holy Book) opens the door for false interpretations, a tendency to believe without weighing the evidence and to resort to innate prejudices. It promotes the acceptance of false history and false science. Creationism, for example.

Moreover, says the writer, it puts into question the merits of the religion itself as a moral teaching.

Yet, you might say, the average person believes a lot of nonsense and half-baked notions. Every day we fill our brains up with rubbish. It's a part of living, unfortunately.

So, is it really worth worrying about? Is there really any harm in this?

Moreover, says the writer, it puts into question the merits of the religion itself as a moral teaching.

Yet, you might say, the average person believes a lot of nonsense and half-baked notions. Every day we fill our brains up with rubbish. It's a part of living, unfortunately.

So, is it really worth worrying about? Is there really any harm in this?

The answer is yes. Definitely yes.

Literalism can short-circuit our rational thought and the objective, rational use of the mind. Literalism can also warp the power of our consciences. It can lead people to believe that slavery is an institution that has been approved by God.

And it can lead to atrocities committed in the name of God. the Crusades and the slaughter of heretics.

Let's not forget that Hitler started his reckless adventure professing to be doing God's work in ridding the world of Jews. In a Reichstag speech in 1938- just before he unleashed his plan to exterminate an entire race, Hitler claimed religion was on his side:

"I believe today that I am acting in the sense of the Almighty Creator. By warding off the Jews, I am fighting for the Lord's work. "

Believing that the Bible is the Word of God can also lead some to believe that certain people were created by God to suffer and doing anything about that condition is defying His will. We have seen this example during the early years of the AIDS crisis.

Or to take a more common, more modern example, that certain diseases or natural calamities are a result of God's wrath. Think Pat Robertson who blamed the devastation caused by 7.0-magnitude earthquake in Haiti as divine retribution on the Haitian people for making a pact with the devil back in the colonial period. Earlier he had made similar claims of God's wrath during Katrina.

Such thinking can lead to the embarrassing spectacle of elected officials quoting Scripture during discussions on climate change. Or country clerks refusing to do their duties simply because of her highly-selective literalist interpretation of the Bible. All manner of confusion and idiocy can take place.

And it can lead us to presidential candidates who believe that gay marriage will destroy civilization and thinks evolution is just a theory equal in scientific value to the Biblical legend of creation and Adam and Eve.

Most importantly, believing in sacred texts so literally- whether that be Christian or Islamic or whatever religion- can lead to a cheapening of the religion by claiming a divine protection against all challenges, against the concepts of reform and against the growth of the human spirit.

It can lead the faithful into justifying their prejudices and their ignorance with misunderstood or misinterpreted words from ancient books.

Most importantly, believing in sacred texts so literally- whether that be Christian or Islamic or whatever religion- can lead to a cheapening of the religion by claiming a divine protection against all challenges, against the concepts of reform and against the growth of the human spirit.

It can lead the faithful into justifying their prejudices and their ignorance with misunderstood or misinterpreted words from ancient books.